When the Weather Change

It’s been well over a month since we last updated an article. The piece on the Chives State really drained so much of our energy; the writing process took almost two weeks, and in its completion, we both agreed that we needed a break from writing.

“We can’t be like this anymore. We need to stop being so depressed.”

A week later, when Yan and I felt that our Elephant Room break had been sufficient enough, we sat down to run through a few potential topics for a new piece. We soon realized something in us had changed: the “usual” interesting events, such as the censorships, the consumption trends and the new memes invented by netizens could no longer attract our interests. Even worse, we found ourselves to be more drowned in the feeling of depression; that “we-are-all-doomed” back noise has now become the theme song that’s playing in our heads all day, every day.

What. Is. Wrong. With. Us?!

Unable to self-diagnose and cure, we decided to shift attention to other people first. Throughout September, we kept having conversations with our Chinese fellows; we asked questions, listened to responses, and soon realized there was a common theme to all of the personal stories at this point: everyone is feeling trapped in straitened circumstances of some sorts, and is losing faith about the country’s, and their own future to varying extents.

Unable to self-diagnose and cure, we decided to shift attention to other people first. Throughout September, we kept having conversations with our Chinese fellows; we asked questions, listened to responses, and soon realized there was a common theme to all of the personal stories at this point: everyone is feeling trapped in straitened circumstances of some sorts, and is losing faith about the country’s, and their own future to varying extents.

The weather has truly changed, and the people are feeling it.

This article is different from the things we wrote in the past. It doesn’t contain purposed research and detailed planning, instead, it simply aims to serve as an honest record of the many personal comments, questions and stories we collected in September. We are not hoping to land on a particular conclusion because we believe in a time that pessimism dominates the overall public atmosphere, it is more important to first understand what other people are feeling, and to think about how we got here, as individuals and a society of collective.

So here we go.

1. Peng

Peng is the kind of folk that we had always looked up to personal-finance wise. With a self-driven interest in investment, he started to game in the Chinese stock market as early as in college, and over the years profited quite a load from it. At the age of 25, he had already purchased his own car and had been preparing to buy an apartment. This is not a small deal, considering that Peng came from a humble family background and had only migrated to Beijing for a few years.

We chatted with Peng two weeks ago. Knowing that he’d been actively looking for apartments in town, we brought up the topic excitingly: “Any new ones you’ve visited recently? Have you made the decision yet?”

“Huh,” Peng squeezed a dry laugh, “plan changed, I am not getting apartment any longer. Real estate price is going down so much, plus, I’ve been losing serious money in the stock market. Thanks to Trump and Xi Dada, my trading account is now a bloody disaster.”

Domestic economic stagnation along with the trade war have taken a toll on China’s stock market.

“Well…But surely you had saved up some already? Since you are no longer buying a house, maybe you can splurge on other things and enjoy life better? Go on holidays! Upgrade your consumption!” Yan encouraged.

“Haha, upgrading?!” Peng sounded bitterer than ever, “I just cancelled my holiday flight tickets to Bali and closed most of my stock accounts in order to save money! The domestic market is f*cked and I am exchanging most of my cash into U.S dollars. No more room for personal financial gain. I must start to save carefully from now on.”

2. Mr. Zhang

Ever since I was little, I’ve been hearing a lot of legendary stories about Mr. Zhang, the renowned businessman and a long-time friend of my father. As the founder of one of the most reputable real estate companies in Xi’an, Mr. Zhang had been developing residential buildings in Shanxi province for almost two decades, and all of his properties sold in the blink of an eye.

But everything changed this year. When I met with Mr. Zhang on a dinner last month, he looked extremely tormented with eyebrows tightened. “My company is in real trouble now”, he stared emptily into the food plates on our table, “the new apartment building we put on the market two months ago has only managed to sell about 1/10 this far. If we couldn’t get it completely sold by the end of this season, we’d literally go bankrupted for the loans we couldn’t repay.”

In June 2018, the Shanxi government announced a new set of restriction policies for house purchase in the province – something authorities have been doing all across China over the past two years. The measures banned certain groups of clients, in particular those without Xi’an hukou and already owned one unit of property in the province, from participating in the house-purchase lottery system. “Our apartment is located on the outskirt of Xi’an and designed luxuriously. The original intention was to sell to wealthy middle-class families, which mostly consists of immigrants from other provinces hence without local hukou. The new restriction polices really f*cked us up – for the first time in my career as a real estate developer, I am faced with a situation of NOT being able to sell. We are doomed. The whole domestic industry is doomed.”

Mr. Zhang was not exaggerating. In September, Vanke, one of the largest real estate companies in China, held their seasonal shareholder meeting titled “We Must Survive 活下去” – a ghastly cry out for the desperate market situation. On September 26th, Vanke announced a half-sale on its property in Xiamen, which slashed the original 5 million RMB price-tag to 2.78 million. Developers in other cities have also been announcing discounts, one in Shanghai even offered free BMW vehicle for new clients.

With tighter financing constraints, a state campaign to rein in housing prices and the tumbling RMB since the trade war, the Chinese real estate market is falling into its coldest winter. Developers with tough repayment pressure are now walking on a tightrope that could virtually bankrupt them anytime, and the consumers, who have lost faith about their property values or simply unable to make purchase due to government restrictions, are quickly leaving the game.

With tighter financing constraints, a state campaign to rein in housing prices and the tumbling RMB since the trade war, the Chinese real estate market is falling into its coldest winter. Developers with tough repayment pressure are now walking on a tightrope that could virtually bankrupt them anytime, and the consumers, who have lost faith about their property values or simply unable to make purchase due to government restrictions, are quickly leaving the game.

3. Li

With a foreign passport and a few years of working experience in the finance industry, Li is now helping her father to take care of the family business. Young, wealthy and capable, Li seemed to be the last one to worry about the economy – at least that was what we naively thought before talking to her.

“Are you kidding? The environment for the private sector is so hostile now that my father is seriously considering about early retirement.”

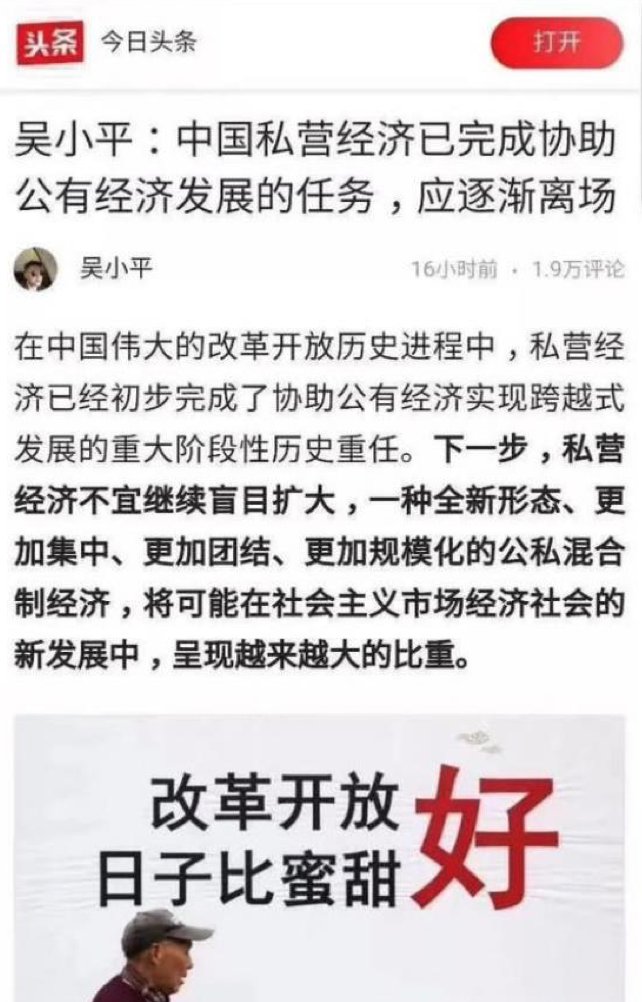

In September, an article named “Private Corporate Should Phase Out” went viral on Chinese social media. Written by Wu Xiaoping the self-claimed finance expert, it declared that private entrepreneurship in China had done playing its historical role, and called on the country to embrace state-private mixed ownership in the future. Although the piece was soon deleted and criticized by state media, its title alone struck the nerve of people in China’s private sector, including the two of us.

“Of course the officials would deny such notion, but verbal denial is not enough to ease our anxiety. We are not fools! It is more than obvious that the government has decided to give us private businesses a hard time. I for one fear that we might not even be able to afford paying our employees next year!”

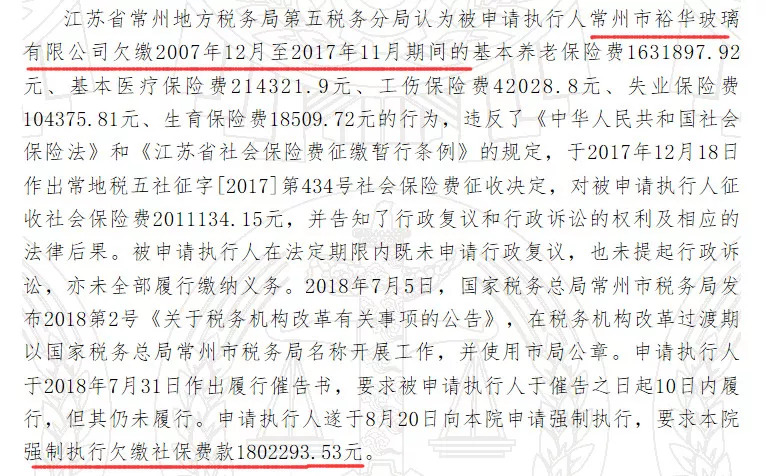

What Li was referring to is the social security reform, an effort to “crack down tax evasion” (“more like the government is bankrupted and using excuse to squeeze from us!” Said Li.) by scrutinizing private companies’ social-security contributions for their employees. The measures were announced to entry into force next January, and would be deadly for small to medium sized corporates due to the dramatic rise in labor cost.

Li’s company has over 200 full-time employees. In the past, Li as the employer had the room to negotiate with its employees in terms of the level of social security tax to be paid by the company. “Yes, we do pay less than the required level for some of them, but it’s totally consensual. Our HR would discuss with every employee upon their hiring, and for those accept us to pay less, we’d compensate through cash. It’s mutual and transparent, I’d even say it’s a win-win situation.”

According to Bloomberg, as of 2018, only 27 percent of firms in China pay their social society obligations in full. The evasions are for a good, or at least understandable reason: the tax is too much. In Beijing for instance, companies must pay 19 percent of an employee’s wage base in pension contributions, and another 10 percent for medical insurance. “We don’t want to do things this way, but tell me, what other ways can we do things?! ” Li shook her head and signed heavily.

“Well, not all private businesses are doomed. Those running immigration agencies are in honeymoon now!” Li laughed, “Netizens used to joke about immigrating every time a stigmatized event occurred, now, people are really moving abroad. A neighbor of ours was planning to buy a new house for her daughter, after a conversation with my dad she has now decided to use that money for immigration instead. Certainly wise I must say!”

4. Tao

It was a long day in the office. While Yan and I sat in the meeting room for some internal discussions, our colleague Tao, the editor-in-chief of our Chinese media platform, knocked the door.

“What’s wrong?” I sensed bad news from the anxiety on Tao’s face.

“The article we posted yesterday got deleted. There’s no explanation given, but I am guessing it’s because of its title.”

Tao must be right. The article itself was merely a weekly news rundown of the domestic real estate market, something we’ve been publishing regularly for months. Yet its title, “What’s going on behind the crash of long-term rental apartment market?” got on the nerve of the internet police. “I just chatted with my friend who also works for internet media”, Tao said, “apparently ‘long-term rental apartment’ is a sensitive keyword now after the market went downslope. I am so sorry! I should have been aware of it.”

How is it Tao’s fault? Graduated with a degree in politics and worked in state-owned newspaper previously, Tao is the kind of editor-in-chief that always knew the boundaries. In fact, his political sensitivity is a key reason that our company’s Chinese media platform, one that focuses on domestic business and finance with over a million subscribers, got to survived until this day. Tao has managed to keep our platform in the safe zone, making sure none of our content would be subjected to the risk of censorship – until this time.

In recent weeks, the boundaries between what can and cannot say have been increasingly blurred. In fact, any content with the slightest hint on the domestic economic situation would risk being censored, or even the entire social media account being banned.

“By the way, have you guys heard about what’s going on with Kungfu Finance (a famous self-media account focuses on finance)?” Tao asked, “their WeChat account was banned from publishing for a month because of a commentary they wrote regarding the new taxation policies. The piece received a large amount of views, and it was hinting in the lightest way that the new policies could be harmful to the private sector. Seriously, how can a media business survive any longer if they cannot post anything?!”

We wonder just the same as Tao, but we also can’t help to wonder about another question: in a political climate like today, what’s the point for a media to survive anyway, if all it is thinking about is how to bypass censorship and to stay alive?

This is one, among many other questions we don’t have answers for in today’s China.

“Survival desire”, the dominant theme for Chinese private businesses today.