Wukong’s Water Curtain Cave: When an IP Steps Into the Real World

Want to read in a language you're more familiar with?

The spectacle is striking not just for its success, but for what it represents: an experiment in breaking boundaries—between virtual and physical, between fan enthusiasm and brand strategy.

At six in the morning, the air in Hangzhou’s Yichuang Town still carries the scent of osmanthus. Wu you sets down a folding stool beneath the bronze statue of Zhong Kui riding a tiger. The line ahead of him moves barely three meters every half hour, curling twice around the park fence. By ten o’clock, when the BLACK MYTH store finally opens, Chen’s palms are sweating around his phone—he’s here for the Xiangfei gourd pendant, rumored to be limited to just three hundred pieces.

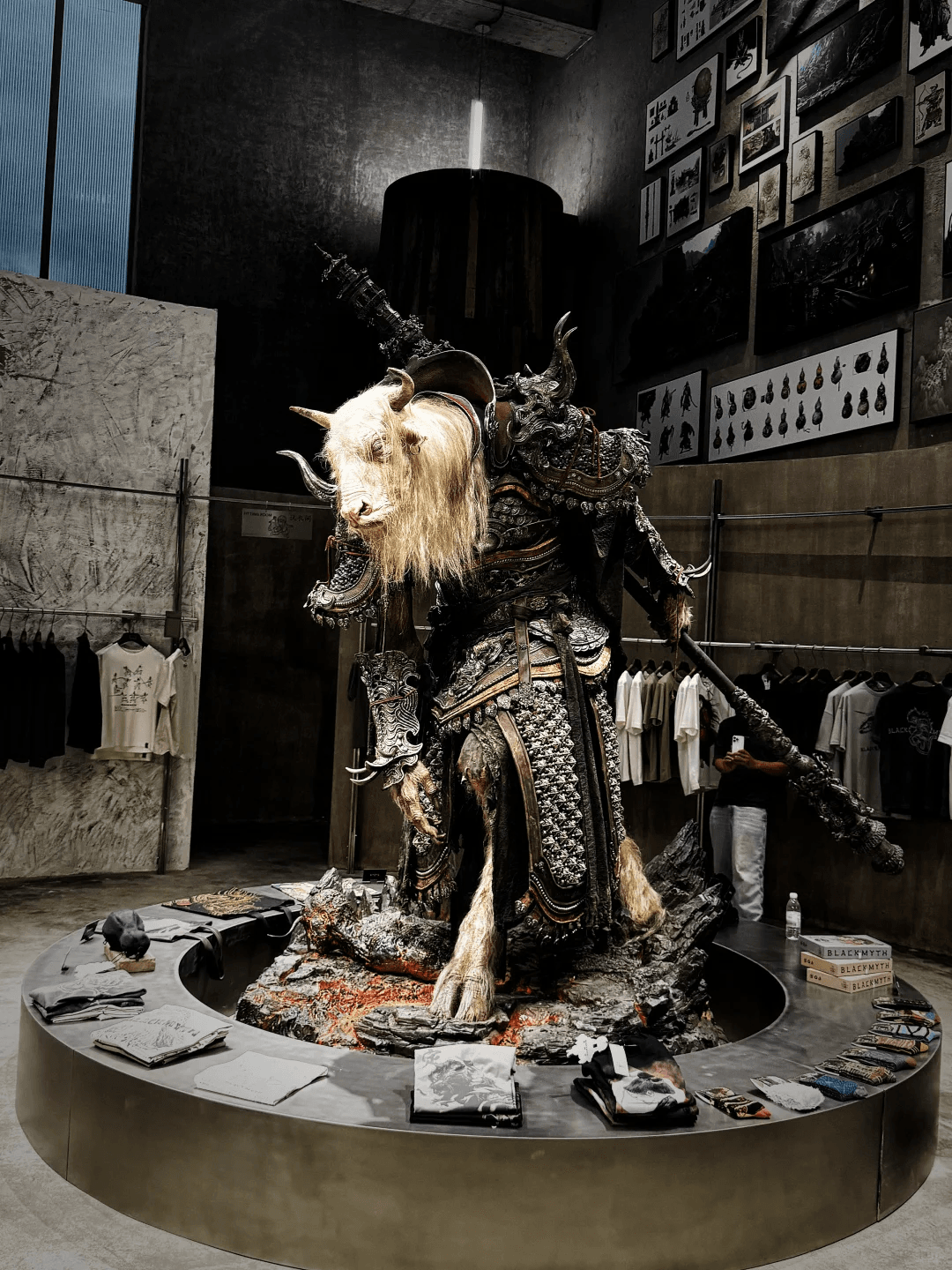

Inside, the air smells of coffee and polished wood. A sales assistant balances on a ladder to restock; the Monkey King pendants have sold out for the third time that morning. In one corner, visitors crowd around a floor tile that flashes red when stepped on—a “hidden Easter egg” with over twenty million views on social media. The limited “Yellow Wind Demon King” figurine sells for ¥3,999, though scalpers outside are already flipping it for ¥5,000. By the end of the month, the store has welcomed over 80,000 visitors, with average per-capita spending of ¥320—more than double that of most cultural merchandise shops.

The spectacle is striking not just for its success, but for what it represents: an experiment in breaking boundaries—between virtual and physical, between fan enthusiasm and brand strategy.

From Wukong to Zhong Kui: Refusing to Settle, Learning to Grow

The offline store wasn’t a spontaneous stunt. It coincided with another bold move by Game Science, the studio behind Black Myth: Wukong. A month before the store opened, the company shocked fans by announcing that it would not release the much-anticipated Wukong DLC. Instead, it revealed a new title: Black Myth: Zhong Kui. The decision came after Wukong sold 22 million copies worldwide and generated $1.1 billion in revenue. Founder Feng Ji wrote candidly that he had felt “lost and fearful” amid the pressure for expansion. The turning point came when art director Yang Qi suggested a different path—“a story we still need to tell.” The team agreed to abandon the easy sequel in favor of a fresh start. As Feng put it, Zhong Kui would bring “clarity and renewal,” allowing the team to rethink what they had done—and what they hadn’t. Culturally, the choice runs deep. In Chinese folklore, Zhong Kui is the exorcist and judge of the underworld, both fierce and righteous. Game Science embraced this duality, hoping to help global players grasp the mythic texture of their new world.

What links the store and the new game is a shared instinct: to grow outward, not merely upward. When most studios double down on DLCs to extend an IP’s shelf life, Game Science expands in two opposite directions—one diving deeper into culture, the other pushing the game’s universe into tangible space.

The Missing Frontier: Why Game Science can be the first?

That the Black Myth store exists at all is already a kind of rebellion. Few Chinese game giants dare to venture into heavy, physical investments. Take miHoYo. Despite Genshin Impact’s immense cultural reach, its offline presence remains limited to pop-up exhibitions and merchandise shelves. The reasoning is economic: offline retail simply can’t compete with in-game monetization. Tencent, too, stays cautious, scarred by the early-2000s failure of Shanda’s game-themed parks—expensive, confusing, and short-lived. Instead, Tencent licenses its IPs to exhibitions, outsourcing both the risk and the storytelling.

By contrast, global models like Disney or Nintendo show what’s possible when storytelling becomes infrastructure. A Disney park is not a “shop”; it’s an emotional engine, transforming products into symbols of belonging. The Nintendo flagship in Tokyo demonstrates similar precision: a thousand-square-meter arena where AR-powered Mario photo booths blur the line between play and presence. The key insight is simple—offline space is not about selling merchandise, but about extending the universe itself.

Game Science’s DNA: Never Say Never

The store, then, is not a marketing gimmick but a continuation of Game Science’s founding logic. Its DNA was never “opportunistic innovation,” but a stubborn pursuit of cultural weight and experiential depth. In 2014, when Feng Ji and his team left Tencent’s Asura project at the height of the mobile game boom, they did so out of disillusionment—with how profit had eroded purpose. They vowed to build games that mattered. By 2018, as China became Steam’s largest user base, they committed to developing a domestic 3A title—at a time when such ambition seemed naïve. “If others can make a great 3A game,” Feng once said, “why can’t we?”

They spent years scanning temples, carving digital stone from real ruins, embedding texture and ritual into code. That same devotion now manifests physically. The offline store borrows the logic of a 3A world: meticulous realism, symbolic detail, and emotional immersion. Every object—the bare feet of Zhong Kui’s tiger, the cracks on the Bull Demon statue—is touchable storytelling. Even the tile that glows underfoot continues the Wukong ethos: “The world hides in the smallest details.”

Just as 3A development demands long-term investment, the store’s business model prizes durability over speed. Instead of licensing, Game Science runs it directly, curating monthly art shows and maintaining narrative coherence. Membership data reveals the payoff: over 200,000 registered users and a 40% higher repurchase rate among members. Like its games, the store doesn’t seek quick profit—it builds roots. Rejecting the Wukong DLC and opening a physical store stem from the same principle: don’t exhaust the soil; plant something new. If the former resists overharvesting an IP, the latter gives it space to grow—across mediums, across realities.

Planting Trees, Leaving Space

In an interview, Feng Ji said, "I don’t think 'Chinese stories' only refer to China’s traditional tales or stories passed down since ancient times. Our company has an external slogan: 'Global Quality, Chinese Story'."

The birth of Black Myth: Wukong is not only a legend of a clever monkey that survived hardships, attained nirvana, and became a deity, but also a story of a group of Chinese game developers who, after once going with the tide, rediscovered their original aspiration. For Feng Ji, the moment the game was launched, marked the end of the first chapter of Black Myth—there are more quests waiting for him to clear in the future. The Great Sage (Sun Wukong) embarks on the Journey to the West once again. Fortunately, while players wait for the Great Sage’s return, Game Science has left such a "Water Curtain Cave" in Hangzhou for them. (Author: Chenhan Zhang)